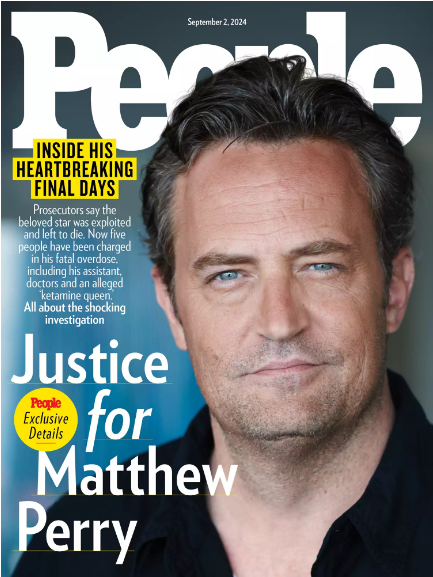

The L.A.P.D. worked with federal agencies to find out how the ‘Friends’ star, who died of an accidental overdose last year, obtained lethal amounts of ketamine

Before Matthew Perry died of an accidental drug overdose at his home in L.A.’s Pacific Palisades neighborhood last Oct. 28, many close to the 54-year-old Friends star believed he was doing well.

Just the year before, in his memoir Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing, the actor—writing with the dry wit that earned him millions of fans around the globe—chronicled his debilitating dependency on alcohol and painkillers, which he abused for much of his adult life.

Explaining to People why he told his story, he said, “I wanted to share when I was safe from going into the dark side again.”

But addiction, that pernicious disease, never loosened its grip. At about 8:30 a.m. on the day he died, Perry asked his live-in assistant, Kenneth Iwamasa, to inject him with ketamine, a quick-acting anesthetic and Schedule III controlled substance that only medical professionals can legally administer.

A bit more than four hours later, the actor wanted a second shot while he watched a movie. Perry then asked Iwamasa to prepare his hot tub for use and inject a third dose: “Shoot me up with a big one,” he said, according to court documents filed by prosecutors and obtained by People.

Iwamasa complied, and left the gated $5 million home to run errands. When he returned that afternoon, Perry was dead, face down in the hot tub.

Nearly 10 months later, on Aug. 15, authorities announced a grand jury had charged Iwamasa, 59, along with four other alleged co-conspirators, in connection with Perry’s death.

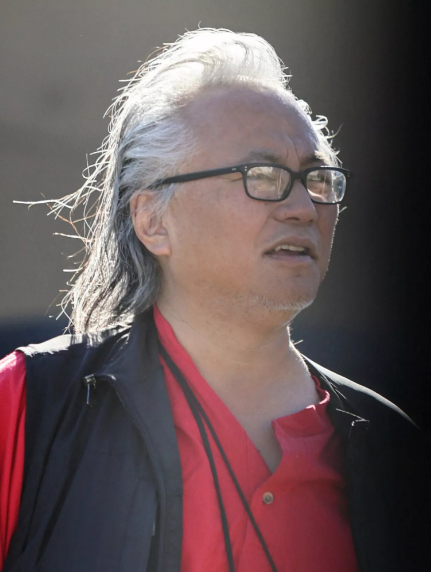

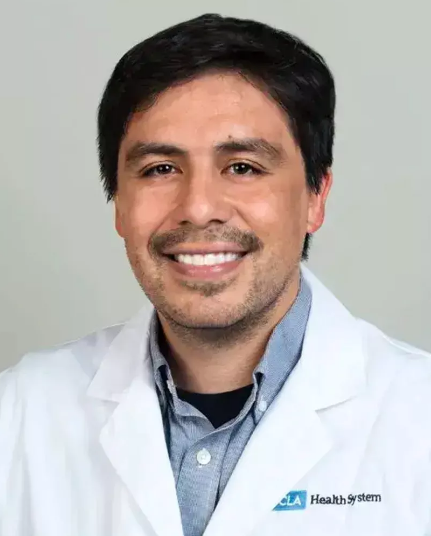

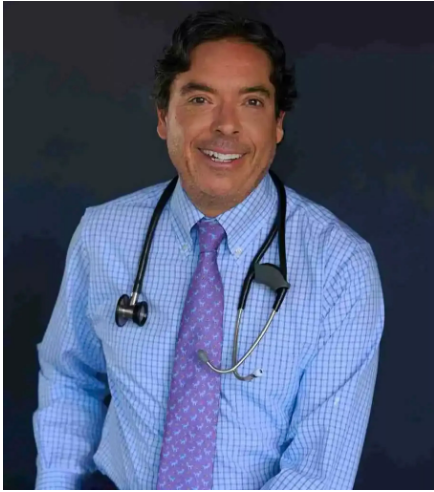

Those who played a “key role,” as DEA Administrator Anne Milgram said in a Los Angeles press conference that day, included Salvador Plasencia, 42, a doctor who sold ketamine to Perry and administered it to him; Mark Chavez, 54, a doctor said to have obtained ketamine for Plasencia from legal suppliers; alleged drug dealer Jasveen Sangha, 41, named in court papers as “The Ketamine Queen”; and Erik Fleming, 54, who allegedly sold Sangha’s supply to Perry’s assistant. Prosecutors claim it was Sangha’s ketamine that killed Perry.

Three of the accused—Chavez, Fleming, and Iwamasa—have taken plea deals. Plasencia and Sangha pleaded not guilty to multiple charges, including distribution of ketamine resulting in death, and face 10 years to life in prison if convicted at trial.

Chavez could be sentenced to up to 10 years in prison, Iwamasa 15 years and Fleming 25 years. Milgram excoriated the accused for preying on Perry, especially physicians Plasencia and Chavez, whom she called “unscrupulous doctors who abused their position of trust because they saw [Perry] as a payday.”

The charges came after a joint investigation by the Los Angeles Police Department and federal agencies, who began their painstaking work after Perry’s autopsy determined his cause of death to be “acute effects” of ketamine. (Contributing factors included drowning, coronary artery disease and the effects of buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid addiction.) “

The detailed court documents show the dark world of drug dealing while also painting a devastating picture of Perry’s final weeks alive. While he regularly played pickleball and caught up with old friends like Friends creator Marta Kauffman, who said he seemed “happy and chipper,” Perry secretly spent tens of thousands of dollars on ketamine and took the drug up to eight times per day.

In his memoir, Perry wrote about previously using the drug as a treatment at a Swiss rehab clinic, saying was it “like being hit in the head with a giant happy shovel. But the hangover was rough and outweighed the shovel. Ketamine was not for me.”

Nevertheless, on Sept. 30, 2023, doctors Plasencia and Chavez, acquaintances for 20 years, learned through intermediaries that Perry was interested in purchasing ketamine, and discussed the deal.

“I wonder how much this moron will pay,” one wrote to the other, according to prosecution court papers. Chavez, who allegedly obtained ketamine with a fraudulent prescription, sold it to Plasencia.

That day, a deal with Perry was made. Plasencia traveled to the star’s newly renovated home overlooking the Pacific Ocean and injected the actor with ketamine and left syringes and more doses with Iwamasa, who paid him $4,500 for the visit, prosecutors say.

Before Plasencia left, he allegedly showed Iwamasa how to administer ketamine to Perry.

Iwamasa, using code words like “Dr. Pepper,” indicated Perry wanted more ketamine in the following days, according to prosecutors, and Chavez and Plasencia were determined to get it for him.

“I think it would be best served not having him look elsewhere and [b]e able to be his go to,” Plasencia allegedly texted Chavez.

According to court papers, Plasencia met up with Perry one afternoon in October to give him more ketamine and injected him while the two were “sitting in the back of a car that was parked in a public parking lot near an aquarium in Long Beach, California.”

On Oct. 12, a scarier incident occurred while Plasencia was administering a dose: Perry had “an adverse reaction” and his blood pressure spiked, according to accounts in the documents.

The drug caused him to “freeze up” temporarily, leaving him unable to talk or move.

Plasencia allegedly told another patient that Perry’s addiction was “spiraling out of control,” says Estrada, the U.S. Attorney for central California. “Yet still at the same time [he was] offering to sell ketamine to Mr. Perry. I think all that conduct shows a level of greed that put the prioritized profits over the patient.”

Around the same time, Chavez learned he was being investigated by the Medical Board of California for allegedly taking ketamine from his former clinic, Dreamscape Ketamine, and cut off his supply to Plasencia.

But by then, Perry was getting drugs through another channel: A Hollywood acquaintance, Fleming—the director of the 1999 Scarlett Johansson movie My Brother the Pig and a producer on the 2003 reality series The Surreal Life—had also allegedly offered to sell Perry ketamine in the weeks leading up to the actor’s death.

Fleming allegedly worked with “Ketamine Queen” Sangha, who prosecutors say lived a glamorous, globetrotting lifestyle while “holding herself out as a celebrity drug dealer with high-quality goods,” including ketamine, methamphetamine and magic mushrooms.

In texts with Iwamasa, Fleming made clear he wanted to earn cash on the drug deals. “I wouldn’t do it if there wasn’t the chance of me making some money,” he allegedly wrote.

And over the following weeks, Perry, through Iwamasa and Fleming, allegedly purchased dozens of vials of ketamine from Sangha, including the final dose that killed the actor on the morning of Oct. 28.

Shortly after Perry died, an alleged cover-up unfolded. Sangha and Fleming spoke via the encrypted Signal app and agreed to distance themselves from the deal by deleting all previous messages.

And Fleming later spoke with Iwamasa, who confirmed he cleaned up the scene of Perry’s death, eliminating evidence of syringes and ketamine vials, according to the court papers. Plascencia, meanwhile, allegedly falsified medical records by writing a supposed “treatment plan” for Perry.

In another conversation with Sangha, Fleming seemingly laid the groundwork for pointing a finger at Iwamasa. “I never dealt with [Perry]. Only the Assistant. So the Assistant was the enabler,” he wrote.

But the way authorities see it, all five parties are responsible for Perry’s death.