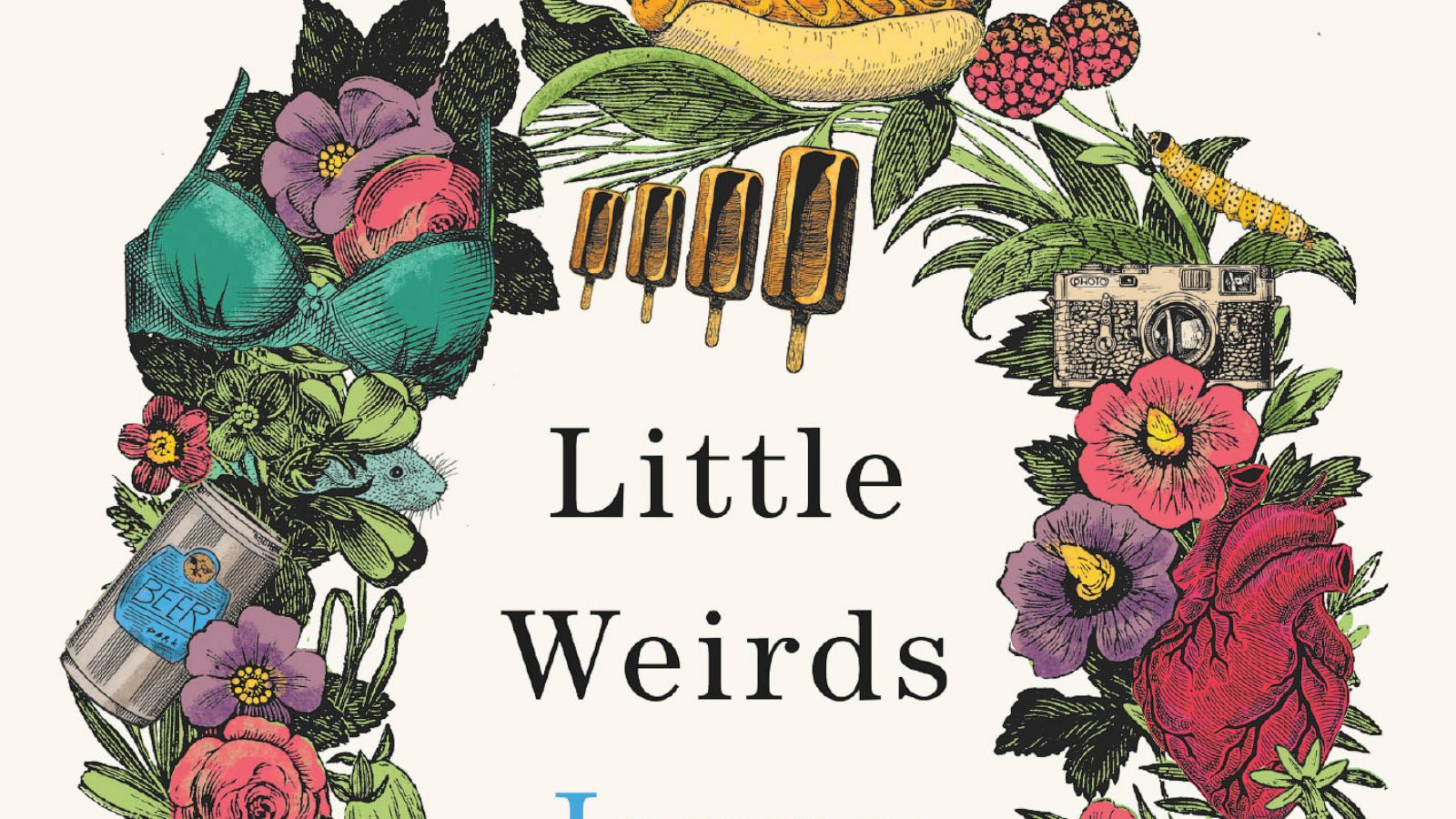

The actress and comedian Jenny Slate opens her memoir-in-essays Little Weirds with an “Introduction/Explanation/Guide for Consumption” — a description of her stage fright, which doubles as a description of her nerves about writing a book.

“On stage and everywhere else,” she writes, “I know there is so much you could do to me. My vulnerability is natural and permissible and beautiful to me, and it should remind you of your responsibility to behave like a friend to me and the world.” Later in the introduction, she puts an even finer point on it, writing, “I’m setting the tone and the tone is this: There is a free, wild creature up here, and now you must think about how to take her in and keep her alive.”

All Slate’s tone-setting puts a critic in a tough position. If I dislike Little Weirds, or find it in various ways wanting, am I no longer a friend to the world? Am I guilty of killing wild creatures? Or can I be a friendly, wild-creature-loving accepter of vulnerability and still wish that Little Weirds demonstrated more of the tonal range, irreverent wildness, and utter self-exposition that characterize Slate’s stand-up?

I do wish all of the above. Mostly, I wish that Little Weirds were weirder, and more intimate. In Slate’s new Netflix special, Stage Fright, she mixes decades-old home videos and filmed interviews with her family members into the live stand-up set she performs. The result is pleasingly choppy and highly personal. It keeps the viewer both off-balance and engaged. Little Weirds, in contrast, slides by smoothly and vaguely. Slate’s essays tend toward the short, casual, and mildly silly, and her language strikes a balance between oddly flat statements and endearingly specific word choices enlivened by the occasional Seussian rhyme, as when she declares that she will no longer engage in “rude and crude struggle[s].” But Slate’s rhymes and specificities disguise the fact that her essays’ content is quite mainstream and sometimes fuzzy. She writes, without much detail, about the end of her marriage, her grief over Donald Trump’s electoral victory, the joy she takes in family and friendship, her hopes for a bright romantic future, and her steps toward self-acceptance and self-love.

These are topics that could easily lend themselves to fun, rowdy, strange writing, but only if Slate were as open to self-exposure on the page as she is in her stand-up. Because she shies away from it in Little Weirds, however, her essays often fall a bit flat. Take “Geranium,” which opens, “A mistake has been made about wildness.” Wildness, Slate decides, is “holy.” It “belongs in people” and “in the home.” This revelation comes not in the context of her own wildness, but that of geraniums blooming inside a castle. To Slate, these geraniums demonstrate that we should “bring wildness [inside] and care for it.” She gives instructions: “Place a shell in your shower. Get a whole plant in there. Put a geranium in your kitchen. Stand in your space and howl out.” This reads, to me, less like weirdness than like mild self-help — which is, ultimately, Little Weirds‘ dominant ethos.

Fundamentally, Slate’s purpose in Little Weirds seems to be steering the reader toward finding his or her own vulnerability as “natural and permissible and beautiful” as she finds her own. This is admirable, but not strange. Even Little Weirds‘ experiments tend to contain ideas that are not experimental at all. Take the essay “Fur,” which opens “I dreamed I lifted up my little breasts and lining their undersides was a soft white- and toffee- colored fur.” The fur is “soft and clean,” and touching it is like touching “a dearness for and in myself.” This may seem odd, but it becomes familiar the moment Slate gets to the dream’s root. She wants to be “the real animal of myself” — a desire that should be recognizable to anyone who’s read the poet Mary Oliver’s beloved “Wild Geese,” which opens:

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Like Oliver, Slate equates self-acceptance with animal nature, and equates animal nature with softness. Fair enough — but not wild, or weird.

Little Weirds is full of soft and lovely moments. In “Beach Animals,” Slate beautifully evokes the pleasures of female friendship, and in “I Died: Sardines,” she delightedly evokes the pleasures of sardine sandwiches. In “Sit?” she watches “a little boy put his puppy on a skateboard and say, ‘Patrick. Sit?'” I may be a hard-hearted wild-creature-killer, but even I am not immune to the charms of a skateboarding puppy named Patrick. I am, however, disinterested in loveliness for its own sake. I prefer Slate in Stage Fright, in which she imitates skeletons, invites viewers into her grandmother’s closet, and talks about sex in an alarming and hilarious baby voice. Those weirds are the right weirds for me.

Lily Meyer is a writer and translator living in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Image Source:*abcnews.go.com

Source:npr.org